Review: Stealing My Religion

The following review was originally published in the Journal of Unitarian Universalist Studies 46, no. 1 (2023). A downloadable version of the review is available here. The book is available from Harvard University Press.

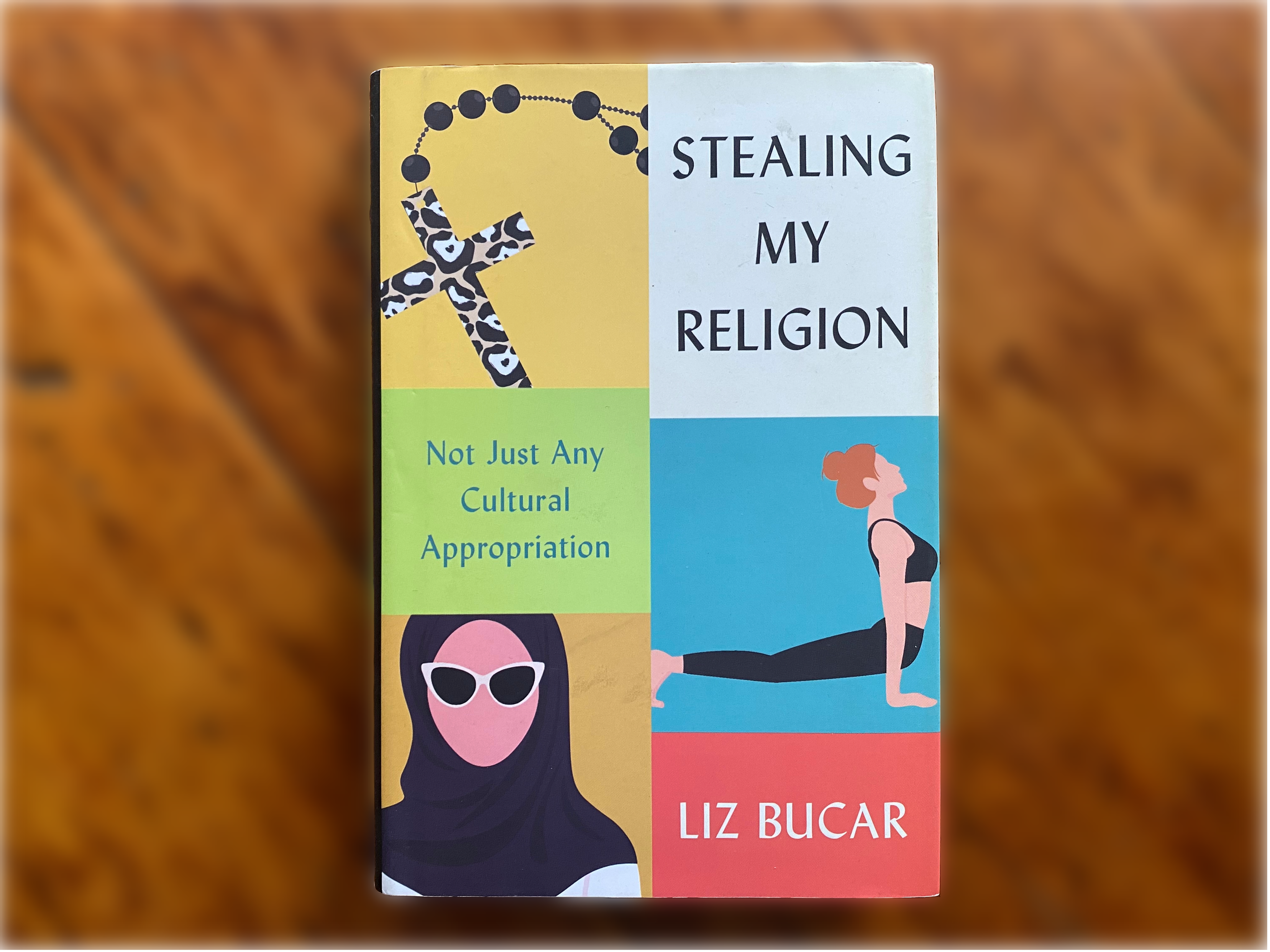

Image of the front cover featuring above different colored blocks: a cross, a person in a yoga pose, and a person in a hijab.

Stealing My Religion: Not Just Any Cultural Appropriation. Liz Bucar. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2022. 272 pp. $24.94 (cloth), $23.69 (Kindle).

In this fascinating new book, Liz Bucar, a professor of religion at Northeastern University who focuses on ethics, points to how Americans consistently engage in what she terms “religious appropriation.” Bucar defines religious appropriation as adopting “religious practices without committing to religious doctrines, ethical values, systems of authority, or institutions, in ways that exacerbate existing systems of structural injustice” (2). As global society becomes evermore integrated and pluralistic, Bucar highlights who might be stealing from whom. She challenges the reader to think critically about the ethics behind religio-spiritual practices. Offering three case studies, Bucar explores aspects of American culture that touch most readers. To Bucar, it is especially important to consider how the term “appropriation” might be more effectively employed. So often wielded accusatorially, shutting down any meaningful conversation, she notes, “appropriation” should instead be the starting point of investigation.

The introduction features a thorough explanation of her intended aims alongside clarifying definitions. Drawing on work done by Malory Nye in Religion: The Basics, Bucar elegantly demonstrates how religion is something we do, defining religion as a verb rather than as simply a noun. Bucar proceeds by problematizing the popularly understood division between “spiritual” and “religious” and suggests that the dichotomy “eases the way for appropriating the religious practices of others … Since we are only adopting the bits that ‘work for us,’ without buying into doctrines, dogmas, or values, we assume we can safely remain outsiders” (25). Bucar echoes Robert Bellah’s 1985 elaboration of “Sheila-ism,” an individualistic gathering of practices from a variety of traditions. In Habits of the Heart, Bellah outlines a trend where individuals take practices and beliefs from a wide variety of religions with little regard for the underlying traditions and histories (Stealing My Religion similarly takes the time to query the ethics of this and similar phenomena).

The first case study centers on how the hijab has been wielded by non-Muslim women to signal allyship. Here, Bucar critiques the concept of what she terms the “solidarity hijab.” Many Muslims have identified this practice as a harmful version of allyship. Bucar explains how solidarity hijab brings to the fore a variety of often-intersecting oppressions: orientalism, white feminism, anti-black racism, and American nationalism.

Second, Bucar tackles the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in Galicia, Spain. Critically engaging history, Bucar highlights the complex religious dimensions and emergence of this famous devotional pilgrimage. The pilgrimage is centered around the relics of St. James the Greater, one of Jesus’ twelve apostles. Yet Bucar complexifies this history, addressing the convenient appearances of these relics at a time when Christian Spain was being threatened by encroaching Islam. Indeed, depictions of James throughout the Camino, and in the central Cathedral in Santiago de Compostela, show an angelic James on horseback slaughtering Muslims. Bucar goes on to note how today’s pilgrims of varying religious traditions reinterpret and experience this Catholic pilgrimage. Centering the idea of experiential education in the context of religion, Bucar critically analyzes the assumptions brought by students and educators to study-abroad programs and immersive experiences. She asks: what does it mean to step into someone else’s religion to experience it authentically? One important element running through this book is a complication of the very idea of authenticity, positing a more postmodern idea that focuses on the question of affect—does this feel authentic to me?—as opposed to an objective either/or dichotomy.

Lastly, Bucar focuses on the practice of yoga for wellness. A Kripalu yoga practitioner and teacher herself, Bucar distinguishes between devotional and respite yoga. The first is linked with beliefs, rules, norms, and sometimes a monastic lifestyle. The latter is “feel-good yoga for self-care” (147). Respite yoga borrows from the practices of devotional yoga to set a tone of mystical antiquity. The central questions in this chapter reflect ethical concerns that arise at the intersection of health and cultural exchange. Bucar reminds readers that modern yoga is the syncretic product of South Asian traditions, capitalism, and colonialism. Ultimately, this case study calls for deeper engagement with yoga from its practitioners in order to facilitate decolonizing the practice. While not inherently against yoga, Bucar critically reimagines what it means to practice yoga ethically in light of its complex history throughout the world.

For any reader who has ever peripherally engaged with such broad, complicated, and frequently emotionally and intellectually charged subjects as religion and cultural appropriation, it comes as no surprise that “religious appropriation” is complicated. In her conclusion, Bucar poses key questions to open intra- and inter-personal interrogation of the ethics of appropriation: who owns a religious practice? And who has the right to say whether such a practice is permissible? Bucar also highlights what few consider; the internal heterogeneity of religious traditions can make it possible to appropriate one’s own tradition. This is because, as Bucar states, “religious communities are internally diverse and there are competing interpretations of what is considered right practice … Internal debates about the right way to practice a faith can find outward expressions that look like appropriation” (205). Taking an affective approach to appropriation and authenticity, Bucar makes it clear that “appropriation” functions best as an invitation to conversation than as an accusation.

While the argument is convincing and well-crafted and no book or single author can engage every side of a concept, Stealing My Religion would benefit from a thorough engagement with the concept of cultural ownership. Mentioned momentarily throughout the book, the concept is never developed or engaged critically in a way that enhances Bucar’s arguments. Ultimately, this book calls for more scholarship and has opened the door to explore appropriation broadly in the context of religion.

Bucar presents a well-written, thoroughly interesting, and fundamentally persuasive book that will shape the way scholars and the general public think about religious exchange in our globalized societies. One of the most admirable and notable strengths of this book is Bucar’s reflectiveness on her own borrowings and practices through study-abroad experiences of the Camino de Santiago and her practice of yoga. We need, Bucar argues, to examine and identify where these borrowings perpetuate existing systems of injustice. In order to facilitate this, Bucar emphasizes the need to use instances of appropriation as calls to discussion and learning. Stealing My Religion provides readers with some tools to interrogate their own and others’ religious borrowing critically.